What Are the Major Ways in Which Hellenistic Art Differs From Classical Art?ã¢â‹

From left to right:

the Venus de Milo, discovered at the Greek island of Milos, 130–100 BC, Louvre

the Winged Victory of Samothrace, from the island of Samothrace, 200–190 BC, Louvre

Pergamon Altar, Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

Hades abducting Persephone, fresco in the regal tomb at Vergina, Macedonia, Greece, c. 340 BC

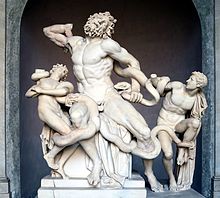

Hellenistic art is the fine art of the Hellenistic period mostly taken to begin with the death of Alexander the Dandy in 323 BC and end with the conquest of the Greek world by the Romans, a procedure well underway past 146 BCE, when the Greek mainland was taken, and substantially catastrophe in 30 BCE with the conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt following the Boxing of Actium. A number of the best-known works of Greek sculpture belong to this period, including Laocoön and His Sons, Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. Information technology follows the period of Classical Greek art, while the succeeding Greco-Roman art was very largely a continuation of Hellenistic trends.

The term Hellenistic refers to the expansion of Greek influence and dissemination of its ideas following the death of Alexander – the "Hellenizing" of the world,[1] with Koine Greek every bit a mutual linguistic communication.[2] The term is a modern invention; the Hellenistic Globe not but included a huge area roofing the whole of the Aegean Ocean, rather than the Classical Greece focused on the Poleis of Athens and Sparta, but besides a huge fourth dimension range. In creative terms this means that there is huge variety which is often put under the heading of "Hellenistic Art" for convenience.

One of the defining characteristics of the Hellenistic menstruum was the sectionalization of Alexander's empire into smaller dynastic empires founded by the diadochi (Alexander's generals who became regents of different regions): the Ptolemies in Egypt, the Seleucids in Mesopotamia, Persia, and Syria, the Attalids in Pergamon, etc. Each of these dynasties proficient a imperial patronage which differed from those of the city-states. In Alexander'due south entourage were three artists: Lysippus the sculptor, Apelles the painter, and Pyrgoteles the gem cutter and engraver.[3] The flow after his death was ane of great prosperity and considerable extravagance for much of the Greek world, at least for the wealthy. Royalty became important patrons of art. Sculpture, painting and architecture thrived, just vase-painting ceased to exist of corking significance. Metalwork and a wide variety of luxury arts produced much fine art. Some types of popular art were increasingly sophisticated.

There has been a trend in writing history to depict Hellenistic art as a corrupt style, following the Golden Age of Classical Greece. The 18th century terms Baroque and Rococo have sometimes been practical to the fine art of this complex and individual period. A renewed interest in historiography every bit well as some recent discoveries, such equally the tombs of Vergina, may allow a better appreciation of the menstruation.

Architecture [edit]

In the architectural field, the dynasties following Hector resulted in vast urban plans and large complexes which had by and large disappeared from city-states by the 5th century BC.[5] The Doric Temple was about abandoned.[vi] This city planning was quite innovative for the Greek world; rather than manipulating infinite past correcting its faults, building plans conformed to the natural setting. One notes the advent of many places of amusement and leisure, notably the multiplication of theatres and parks. The Hellenistic monarchies were advantaged in this regard in that they often had vast spaces where they could build large cities: such equally Antioch, Pergamon, and Seleucia on the Tigris.

Information technology was the time of gigantism: thus it was for the 2nd temple of Apollo at Didyma, situated twenty kilometers from Miletus in Ionia. It was designed by Daphnis of Miletus and Paionios of Ephesus at the end of the 4th century BC, but the construction, never completed, was carried out upwards until the 2nd century AD. The sanctuary is 1 of the largest ever constructed in the Mediterranean region: inside a vast courtroom (21.7 metres by 53.6 metres), the cella is surrounded by a double pillar of 108 Ionic columns nearly 20 metres tall, with richly sculpted bases and capitals.[seven]

Athens [edit]

The Corinthian club was used for the get-go time on a full-scale edifice at the Temple of Olympian Zeus.[viii]

Olynthus [edit]

The aboriginal city of Olynthus was one of the architectural and creative keystones in establishing a connectedness betwixt the Classical and Hellenistic worlds.

Over 100 homes were found at the Olynthus urban center site. Interestingly, the homes and other architecture were incredibly well preserved. This allows us to better sympathise the activities that took place in the homes and how space inside the homes was organized and utilized.

Homes in Olynthus were typically squarer in shape. The desired home was non necessarily large or extravagant, simply rather comfortable and practical. This was a marking of civilisation that was extremely prominent in Greek culture during the Hellenistic menstruation and beyond. Living a civilized life involved maintaining a sturdy living space, thus many brick-similar materials were used in the structure of the homes. Rock, forest, mudbrick, and other materials were commonly used to build these dwellings.

Another element that was increasingly popular during the Hellenistic flow was the add-on of a courtyard to the abode. Courtyards served as a lite source for the home as Greek houses were airtight off from the outside to maintain a level of privacy. There accept been windows found at some domicile sites, only they are typically high off the footing and small. Because of the issue of privacy, many individuals were forced to compromise on light in the home. Well-lit spaces were used for entertaining or more public activeness while the individual sectors of the home were dark and closed off which complicated housework.

Courtyards were typically the focus of the abode as they provided a space for entertaining and a source of light from the very interior of the home. They were paved with cobblestones or pebbles nearly ofttimes, simply there take been discoveries of mosaicked courtyards. Mosaics were a wonderful fashion for the family to express their interests and beliefs too every bit a way to add décor to the home and get in more visually appealing. This artistic affect to homes at Olynthus introduces another element of civilized living to this Hellenistic social club.[9]

Pergamon [edit]

Pergamon in item is a characteristic example of Hellenistic compages. Starting from a simple fortress located on the Acropolis, the various Attalid kings fix a colossal architectural complex. The buildings are fanned out around the Acropolis to have into account the nature of the terrain. The agora, located to the s on the lowest terrace, is bordered past galleries with colonnades (columns) or stoai. Information technology is the beginning of a street which crosses the entire Acropolis: it separates the administrative, political and military buildings on the due east and meridian of the rock from the sanctuaries to the westward, at mid-height, amidst which the about prominent is that which shelters the monumental Pergamon Altar, known every bit "of the twelve gods" or "of the gods and of the giants", one of the masterpieces of Greek sculpture. A colossal theatre, able to contain nearly 10,000 spectators, has benches embedded in the flanks of the loma.[10]

Sculpture [edit]

Pliny the Elderberry, after having described the sculpture of the classical period notes: Cessavit deinde ars ("then art disappeared").[11] According to Pliny'due south assessment, sculpture declined significantly after the 121st Olympiad (296–293 BC). A period of stagnation followed, with a brief revival after the 156th (156–153 BC), but with nothing to the standard of the times preceding it.[12]

Bronze portrait of an unknown sitter, with inlaid eyes, Hellenistic menstruum, 1st century BC, institute in Lake Palestra of the Island of Delos.

During this period sculpture became more naturalistic, and likewise expressive; in that location is an interest in depicting extremes of emotion. On top of anatomical realism, the Hellenistic artist seeks to stand for the character of his subject, including themes such equally suffering, sleep or old age. Genre subjects of common people, women, children, animals and domestic scenes became acceptable subjects for sculpture, which was commissioned by wealthy families for the adornment of their homes and gardens; the Boy with Thorn is an example.

The Barberini Faun, second-century BC Hellenistic or second-century Advertizement Roman re-create of an earlier bronze

Realistic portraits of men and women of all ages were produced, and sculptors no longer felt obliged to depict people equally ethics of beauty or physical perfection.[13] The world of Dionysus, a pastoral idyll populated by satyrs, maenads, nymphs and sileni, had been often depicted in before vase painting and figurines, but rarely in total-size sculpture. The Old Drunk at Munich portrays without reservation an old woman, thin, haggard, clutching against herself her jar of wine.[14]

Portraiture [edit]

The period is therefore notable for its portraits: One such is the Barberini Faun of Munich, which represents a sleeping satyr with relaxed posture and broken-hearted confront, maybe the prey of nightmares. The Belvedere Torso, the Resting Satyr, the Furietti Centaurs and Sleeping Hermaphroditus reverberate like ideas.[15]

Another famous Hellenistic portrait is that of Demosthenes past Polyeuktos, featuring a well-washed confront and clasped hands.[12]

Privatization [edit]

Another miracle of the Hellenistic age appears in its sculpture: privatization,[xvi] [17] seen in the recapture of older public patterns in decorative sculpture.[18] Portraiture is tinged with naturalism, under the influence of Roman art.[19] New Hellenistic cities were springing upwardly all over Arab republic of egypt, Syrian arab republic, and Anatolia, which required statues depicting the gods and heroes of Greece for their temples and public places. This made sculpture, like pottery, an industry, with the consequent standardization and some lowering of quality. For these reasons many more Hellenistic statues have survived than is the case with the Classical period.

Second classicism [edit]

Hellenistic sculpture repeats the innovations of the so-chosen "second classicism": nude sculpture-in-the-round, allowing the statue to be admired from all angles; study of draping and effects of transparency of clothing, and the suppleness of poses.[twenty] Thus, Venus de Milo, even while echoing a classic model, is distinguished by the twist of her hips.

"Bizarre" [edit]

The multi-figure group of statues was a Hellenistic innovation, probably of the 3rd century, taking the epic battles of earlier temple pediment reliefs off their walls, and placing them as life-size groups of statues. Their style is often called "baroque", with extravagantly contorted body poses, and intense expressions in the faces. The Laocoön Group, detailed below, is considered 1 of the prototypical examples of the Hellenistic baroque fashion.[21]

Pergamon [edit]

Pergamon did not distinguish itself with its compages alone: it was besides the seat of a brilliant school of sculpture known as Pergamene Baroque.[22] The sculptors, imitating the preceding centuries, portray painful moments rendered expressive with three-dimensional compositions, oft V-shaped, and anatomical hyper-realism. The Barberini Faun is one example.

Gauls [edit]

Attalus I (269–197 BC), to commemorate his victory at Caicus confronting the Gauls;— called Galatians by the Greeks – had two series of votive groups sculpted: the first, consecrated on the Acropolis of Pergamon, includes the famous Gaul killing himself and his wife, of which the original is lost; the 2nd group, offered to Athens, is composed of small bronzes of Greeks, Amazons, gods and giants, Persians and Gauls.[23] Artemis Rospigliosi in the Louvre is probably a re-create of 1 of them; as for copies of the Dying Gaul, they were very numerous in the Roman period. The expression of sentiments, the forcefulness of details – bushy hair and moustaches hither – and the violence of the movements are characteristic of the Pergamene style.[24]

Great Chantry [edit]

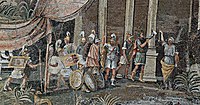

These characteristics are pushed to their peak in the friezes of the Not bad Altar of Pergamon, decorated under the lodge of Eumenes Two (197–159 BC) with a gigantomachy stretching 110 metres in length, illustrating in the rock a verse form composed especially for the courtroom. The Olympians triumph in it, each on his side, over Giants – most of which are transformed into savage beasts: serpents, birds of prey, lions or bulls. Their mother Gaia comes to their assistance, merely can exercise nothing and must spotter them twist in pain nether the blows of the gods.[25]

Colossus of Rhodes [edit]

One of the few city states who managed to maintain total independence from the command of any Hellenistic kingdom was Rhodes. Later on holding out for one yr under siege by Demetrius Poliorcetes (305–304 BCE), the Rhodians built the Colossus of Rhodes to commemorate their victory.[26] With a superlative of 32 meters, information technology was i of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Progress in bronze casting fabricated information technology possible for the Greeks to create large works. Many of the large bronze statues were lost – with the majority being melted to recover the material.

Laocoön [edit]

Discovered in Rome in 1506 and seen immediately by Michelangelo,[27] beginning its huge influence on Renaissance and Baroque art. Laocoön, strangled by snakes, tries desperately to loosen their grip without affording a glance at his dying sons. The grouping is one of very few non-architectural ancient sculptures that tin can exist identified with those mentioned by ancient writers. It is attributed by Pliny the Elder to the Rhodian sculptors Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus.[27]

The central grouping of the Sperlonga sculptures, with the Blinding of Polyphemus; bandage reconstruction of the group, with at the correct the original effigy of the "wineskin-bearer" seen in forepart of the bandage version.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who first articulated the difference between Greek, Greco-Roman and Roman art, drew inspiration from the Laocoön. Gotthold Ephraim Lessing based many of the ideas in his 'Laocoon' (1766) on Winckelmann's views on harmony and expression in the visual arts.[28]

Sperlonga [edit]

The fragmentary Sperlonga sculptures are another series of "bizarre" sculptures in the Hellenistic style, perchance made for the Emperor Tiberius, who was certainly present at the collapse of the seaside grotto in southern Italy that they decorated.[27] The inscriptions suggest the aforementioned sculptors fabricated it who fabricated the Laocoön group,[29] or possibly their relations.

"Rococo" [edit]

The satyr from the Hellenistic sculpture group "The Invitation to the Trip the light fantastic". The sculpture group is seen as a prime example of the "Rococo" trend in Hellenistic sculpture. In the sculpture grouping the satyr was depicted together with a seated female. This sculpture is now in the Musée du Louvre, Paris.

The "Baroque" traits in Hellenistic art, predominately sculpture, have been assorted with a contemporary trend that has been described as "Rococo". The concept of a Hellenistic "Rococo" was coined past Wilhelm Klein in the early on 20th century.[30] Dissimilar the dramatic "Bizarre" sculptures, the "Rococo" tendency emphasized playfull motifs, such equally satyrs and nymphs. Wilhelm Klein considered the sculpture group "The Invitation to the Trip the light fantastic" to be a prime number example of the trend.[31] [32] Also lighthearted depictions of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, and Eros, were seen as typical (as seen, for instance, in the and then-called Slipper Slapper Grouping depicted below). It has afterward been argued that the preference for the "Rococo" motifs in Hellenistic sculpture can be tied to a inverse apply of sculpture in general. Individual sculpture collecting became more than common during the later Hellenistic menstruum, and in such collections there seems to have been a preference for the kinds of motifs characterized as "Rococo".[33]

Neo-Attic [edit]

From the 2nd century the Neo-Attic or Neo-Classical style is seen past different scholars as either a reaction to baroque excesses, returning to a version of Classical style, or equally a continuation of the traditional style for cult statues.[34] Workshops in the style became mainly producers of copies for the Roman market, which preferred copies of Classical rather than Hellenistic pieces.[35]

-

Gravestone of a woman with her child slave attending to her, c. 100 BC (early period of Roman Greece)

-

The so-called Slipper Slapper Grouping: Aphrodite and Eros fighting off the advances of Pan. Marble, Hellenistic artwork from the late 2nd century BC.

-

Hellenistic sculpture fragments from the National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Paintings and mosaics [edit]

Paintings and mosaics were of import mediums in art, just no examples of paintings on panels have survived the autumn to the Romans. It is possible to get some idea of what they were similar from related media, and what seem to be copies of or loose derivations from paintings in a wider range of materials.

Landscape [edit]

Possibly the most striking element of Hellenistic paintings and mosaics is the increased use of mural.[36] Landscapes in these works of art are representative of familiar naturalistic figures while also displaying mythological and sacro-idyllic elements.[37] Landscape friezes and mosaics were usually used to display scenes from Hellenistic poesy such as that by Herondas and Theocritos. These landscapes that expressed the stories of Hellenistic writers were utilized in the home to emphasize that family's education and knowledge about the literary world.[38]

Sacro-idyllic ways that the nigh prominent elements of the artwork are those related to sacred and pastoral themes.[39] This style that emerged about prevalently in Hellenistic art combines sacred and profane elements, creating a dreamlike setting.[40] Sacro-idyllic influences are conveyed in the Roman mosaic "Nile Mosaic of Palestrina" which demonstrates fantastical narratives with a colour scheme and commonplace components that illustrate the Nile in its passage from Federal democratic republic of ethiopia to the Mediterranean. The inclusion of Hellenistic backgrounds can also be seen in works throughout Pompeii, Cyrene, Alexandria. Moreover, specifically in Southern Russia, floral features and branches can be found on walls and ceilings strewn in a matted nevertheless conventional manner, mirroring a late Greek style.[41] In addition, "Cubiculum" paintings found in Villa Boscoreale include vegetation and a rocky setting in the groundwork of detailed paintings of m architecture.

Roman fresco painting known as "Cubiculum" (chamber) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, 50–40 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Fine art 03.14.13a–g.

Wall paintings [edit]

Hellenistic terra cotta funerary wall painting, 3rd century BC

Wall paintings began appearing more prominently in the Pompeian period. These wall paintings were not simply displayed in places of worship or in tombs.[42] Often, wall paintings were used to decorate the habitation. Wall paintings were mutual in private homes in Delos, Priene, Thera, Pantikapaion, Olbia, and Alexandria.[42]

Few examples of Greek wall paintings have survived the centuries. The most impressive, in terms of showing what loftier-quality Greek painting was similar, are those at the Macedonian royal tombs at Vergina. Though Greek painters are given tribute to bringing fundamental ways of representation to the Western World through their art. Three principal qualities unique to Hellenistic painting style were iii-dimensional perspective, the use of light and shade to return class, and trompe-l'œil realism.[43] Very few forms of Hellenistic Greek painting survive except for wooden pinakes panels and those painted on stone. The most famously known stone paintings are establish on the Macedonian Tomb at Agios Athanasios.[43]

Researchers have been limited to studying the Hellenistic influences in Roman frescoes, for example those of Pompeii or Herculaneum. In add-on, some of the paintings in Villa Boscoreale conspicuously repeat lost Hellenistic, Macedonian purple paintings.[44]

Mediums and technique [edit]

Recent excavations from the Mediterranean have revealed the technology used in Hellenistic painting.[45] Wall fine art of this menstruum utilized two techniques: secco technique and fresco technique.[45] Fresco technique required layers of lime-rich plaster to then decorate walls and rock supports.[45] On the other paw, no base was necessary for the secco technique, which used mucilage standard arabic and egg tempera to paint finalizing details on marble or other stone.[45] This technique is exemplified in the Masonry friezes institute in Delos.[45] Both techniques used mediums that were locally accessible, such as terracotta aggregates in the base layers and natural inorganic pigments, synthetic inorganic pigments, and organic substances as colorants.[45]

Recent discoveries [edit]

Contempo discoveries include those of chamber tombs in Vergina (1987) in the former kingdom of Macedonia, where many friezes have been unearthed.[36] For example, in Tomb II archaeologists plant a Hellenistic-style frieze depicting a panthera leo hunt.[46] This frieze institute in the tomb supposedly that of Philip II is remarkable by its limerick, the arrangement of the figures in space and its realistic representation of nature.[47] Other friezes maintain a realistic narrative, such as a symposium and banquet or a armed forces escort, and peradventure retell historical events.[46]

In that location is likewise the recently restored 1st-century Nabataean ceiling frescoes in the Painted Firm at Footling Petra in Jordan.[48] Every bit the Nabataeans traded with the Romans, Egyptians, and Greeks, insects and other animals observed in the paintings reflect Hellenism while various types of vines are associated with the Greek god, Dionysus.[48]

Contempo archaeological discoveries at the cemetery of Pagasae (close to modern Volos), at the border of the Pagasetic Gulf have brought to light some original works. The excavations of this site led by Dr. Arvanitopoulos may be connected to diverse Greek painters in the third and quaternary centuries and describe scenes that allude to the reign of Alexander the Not bad.[49] [50]

In the 1960s, a group of wall paintings was establish on Delos.[51] Information technology is evident that the fragments of friezes found were created by a community of painters who lived during the late Hellenistic catamenia.[52] The murals emphasized domestic ornament, conveying the conventionalities these people held that the Delian establishment would remain stable and secure plenty for this artwork to be enjoyed by homeowners for many years to come.[52]

Mosaics [edit]

Certain mosaics, however, provide a pretty practiced idea of the "grand painting" of the menses: these are copies of frescoes. This art course has been used to decorate primarily walls, floors, and columns.[53]

Mediums and technique [edit]

The evolution of mosaic art during the Hellenistic Period began with Pebble Mosaics, best represented in the site of Olynthos from 5th century BC. The technique of Pebble Mosaics consisted of placing pocket-sized white and black pebbles of no specific shape, in a circular or rectangular panel to illustrate scenes of mythology. The white pebbles -in slightly unlike shades- were placed on a black or bluish background to create the epitome. The black pebbles served to outline the image.[54]

In the mosaics from the site of Pella, from the 4th century BC, it is possible to see a more evolved form of the fine art. Mosaics from this site display the use of pebbles that were shaded in a wider range of colors and tones. They too show early use of terra-cotta and atomic number 82 wire to create a greater definition of contours and details to the images in the mosaics.[54]

Post-obit this example, more than materials were gradually added. Examples of this extended apply of materials in mosaics of the third century BC include finely cutting stones, chipped pebbles, drinking glass and baked clay, known as tessarae. This improved the technique of mosaics past aiding the artists in creating more definition, greater detail, a better fit, and an fifty-fifty wider range of colors and tones.[54]

Example of tesserae used in mosaics.

Despite the chronological order of the advent of these techniques, there is no actual show to propose that the tessellated necessarily adult from the pebble mosaics.[55]

Opus vermiculatum and opus tessellatum were ii different techniques used during this period of mosaic making. Opus tessellatum refers to a redacted tessera (a pocket-sized block of rock, tile, drinking glass, or other fabric used in the construction of a mosaic) size followed by an increased diverseness in shape, color, and material as well equally andamento––or the design in which the tessera was laid. Opus vermiculatum is oft partnered with this technique but differs in complexity and is known to have the highest visual impact.[54]

The majority of mosaics were produced and laid on site. Withal, a number of flooring mosaics brandish the use of the emblemata technique, in which panels of the paradigm are created off-site in trays of terra-cotta or stone. These trays were after placed into the setting-bed on the site.[54]

At Delos, colored grouts were used on opus vermiculatum mosaics, but in other regions this is not common. There is one example of colored grout used in Alexandria on the Dog and Askos mosaic. At Samos, the grouts and the tesserae are both colored.

Studying color here is difficult as the grouts are extremely frail and vulnerable.

Scientifics enquiry has been a source of interesting information with regard to the grouts and tesserae used in Hellenistic Mosaics. Atomic number 82 strips were discovered on mosaics equally a definiting characteristic of the surface technique. Atomic number 82 strips are absent-minded from the mosaics here. At Delos, lead strips were common on mosaics in the opus tessellatum mode. These strips were used to outline decorative borders and geometric decorative motifs. The strips were extremely common on opus vermiculatum mosaics from Alexandria. Considering atomic number 82 strips were present in both styles of surface types, they cannot be the sole characteristic of 1 type or the other.[56]

Tel Dor mosaic [edit]

Detail of mosaic from Tel Dor circa 1st-2nd centuries. Found in Ha-Mizgaga Museum in Kibbutz Nahsholim, Israel.

A rare case of virtuoso Hellenistic mode moving picture mosaic found in the Levantine coast. Through a technical analysis of the mosaic, researchers advise that this mosaic was created by itinerant craftsman working in situ. Since 2000, over 200 fragments of the mosaic have been discovered at the headline of Tel Dor, still, the destruction of the original mosaic is unknown.[57] Excavators advise that earthquake or urban renewal is the cause. Original architectural context is unknown, but stylistic and technical comparisons suggest a late Hellenistic period appointment, estimating around the 2nd one-half of the second century B.C.Eastward. Analyzing the fragments plant at the original site, researchers take constitute that the original mosaic contained a centralized rectangle with unknown iconography surrounded by a serial of decorative borders consisting of a perspective meander followed by a mask-and-garland border.[57] This mosaic consists of 2 unlike techniques of mosaic making, opus vermiculatum and opus tessellatum.[57]

Alexander mosaic [edit]

An instance is the Alexander Mosaic, showing the confrontation of the young conqueror and the Grand King Darius III at the Battle of Issus, a mosaic from a flooring in the Firm of the Faun at Pompeii (now in Naples). Information technology is believed to be a copy of a painting described by Pliny which had been painted past Philoxenus of Eretria for Male monarch Cassander of Macedon at the stop of the 4th century BC,[58] or fifty-fifty of a painting by Apelles contemporaneous with Alexander himself.[59] The mosaic allows us to adore the choice of colors along with the composition of the ensemble using turning movement and facial expression.

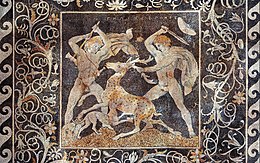

Stag Hunt mosaic [edit]

The Stag Hunt Mosaic past Gnosis is a mosaic from a wealthy home of the late quaternary century BC, the so-called "Business firm of the Abduction of Helen" (or "Firm of the Rape of Helen"), in Pella, The signature ("Gnosis epoesen", i.e. Gnosis created) is the first known signature of a mosaicist.[60]

The emblema is bordered by an intricate floral pattern, which itself is bordered by stylized depictions of waves.[62] The mosaic is a pebble mosaic with stones nerveless from beaches and riverbanks which were fix into cement.[62] Every bit was perhaps ofttimes the case,[63] the mosaic does much to reflect styles of painting.[64] The light figures against a darker background may allude to ruby figure painting.[64] The mosaic also uses shading, known to the Greeks as skiagraphia, in its depictions of the musculature and cloaks of the figures.[64] This forth with its employ of overlapping figures to create depth renders the prototype three dimensional.

Sosos [edit]

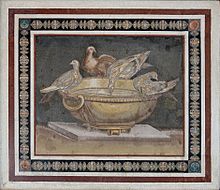

The Hellenistic period is equally the time of evolution of the mosaic as such, particularly with the works of Sosos of Pergamon, active in the 2d century BC and the only mosaic creative person cited by Pliny.[65] His taste for trompe-l'œil (optical illusion) and the furnishings of the medium are found in several works attributed to him such every bit the "Unswept Floor" in the Vatican museum,[66] representing the leftovers of a repast (fish basic, basic, empty shells, etc.) and the "Dove Basin" (fabricated of small opus vermiculatum tesserae stones)[67] at the Capitoline Museum, known by means of a reproduction discovered in Hadrian'due south Villa.[68] In it i sees iv doves perched on the edge of a gilt bronze basin filled with water. One of them is watering herself while the others seem to be resting, which creates furnishings of reflections and shadow perfectly studied by the artist. The "Pigeon Basin" mosaic panel is an emblema, designed to be the central signal of an otherwise plainly mosaic floor. The emblema was originally an import from the Hellenistic eastern Mediterranean, where, in cities such equally Pergamom, Ephesus and Alexandria, at that place were artists specializing in mosaics.[67] 1 of them was Sosos of Pergamon, the most celebrated mosaicist of artifact who worked in the 2d century BC.[67]

Delos [edit]

According to the French archaeologist François Chamoux, the mosaics of Delos in the Cyclades stand for the zenith of Hellenistic-period mosaic art employing the use of tesserae to form complex, colorful scenes.[69] This style of mosaic continued until the end of Antiquity and may have had an bear upon on the widespread use of mosaics in the Western world during the Middle Ages.[69]

-

-

-

Fragments of mural paintings from Delos, c. 100 BC

-

The Sampul tapestry, a woollen wall hanging from Lop County, Hotan Prefecture, Xinjiang, China, showing a possibly Greek soldier from the Greco-Bactrian kingdom (250–125 BC), with blueish eyes, wielding a spear, and wearing what appears to be a diadem headband; depicted to a higher place him is a centaur, from Greek mythology, a mutual motif in Hellenistic art;[seventy] Xinjiang Region Museum.

-

particular of Nabataen ceiling frescoes painted on plastered ceiling.

Pottery [edit]

The Hellenistic Age comes immediately after the great historic period of painted Ancient Greek pottery, perchance because increased prosperity led to more use of fine metalware (very little now surviving) and the decline of the fine painted "vase" (the term used for all vessel shapes in pottery). Most vases of the menstruation are black and uniform, with a shiny advent approaching that of varnish, decorated with simple motifs of flowers or festoons. The shapes of the vessels are frequently based on metalwork shapes: thus with the lagynos, a wine jar typical of the period. Painted vase types that continued production into the Hellenistic period include Hadra vases and Panathenaic amphora.

Megarian ware [edit]

It is also the period of and so-chosen Megarian ware:[72] mold-made vases with ornament in relief appeared, doubtless in simulated of vases made of precious metals. Wreaths in relief were applied to the trunk of the vase. One finds too more than complex relief, based on animals or legendary creatures.

West Slope ware [edit]

Red-figure painting had died out in Athens by the stop of the 4th century BC to be replaced by what is known as West Slope Ware, and so named after the finds on the due west slope of the Athenian Acropolis. This consisted of painting in a tan coloured slip and white paint on a fired black skid background with some incised detailing.[73]

Representations of people diminished, replaced with simpler motifs such as wreaths, dolphins, rosettes, etc. Variations of this fashion spread throughout the Greek world with notable centres in Crete and Apulia, where figural scenes continued to exist in demand.

Apulian [edit]

Gnathia vases [edit]

Gnathia vases nonetheless were still produced not only in Apulian, but as well in Campanian, Paestan and Sicilian vase painting.

Centuripe vase in Palermo, 280–220 BC

Canosa ware [edit]

In Canosa di Puglia in South Italia, in 3rd century BC burials one might find vases with fully three-dimensional attachments.[74] The distinguishing feature of Canosa vases are the h2o-soluble paints. Blue, red, yellow, low-cal purple and brown paints were practical to a white ground.

Centuripe ware [edit]

The Centuripe ware of Sicily, which has been called "the last gasp of Greek vase painting",[ane] had fully coloured tempera painting including groups of figures applied after firing, reverse to the traditional practice. The fragility of the pigments prevented frequent use of these vases; they were reserved for use in funerals, and many were purely for brandish, for example with lids that did not elevator off. The practice perhaps continued into the 2nd century BC, making it possibly the terminal vase painting with significant figures.[75] A workshop was agile until at least the 3rd century BC. These vases are characterized by a base painted pink. The figures, often female person, are represented in coloured clothing: blueish-violet chiton, yellow himation, white veil. The style is reminiscent of Pompeii and draws more from grand contemporary paintings than on the heritage of the red-effigy pottery.

Terracotta figurines [edit]

Bricks and tiles were used for architectural and other purposes. Production of Greek terra cotta figurines became increasingly important. Terracotta figurines represented divinities as well every bit subjects from contemporary life. Previously reserved for religious employ, in Hellenistic Greece the terra cotta was more oftentimes used for funerary and purely decorative, purposes. The refinement of molding techniques made information technology possible to create true miniature statues, with a high level of detail, typically painted.

Several Greek styles continued into the Roman catamenia, and Greek influence, partly transmitted via the Aboriginal Etruscans, on Ancient Roman pottery was considerable, especially in figurines.

A grotesque woman holding a jar of vino, Kertch, second half of 4th century BC, Louvre.

Tanagra figurines [edit]

Tanagra figurines, from Tanagra in Boeotia and other centers, full of lively colours, about often represent elegant women in scenes full of charm.[76] At Smyrna, in Asia Minor, two major styles occurred side-by-side: kickoff of all, copies of masterpieces of bang-up sculpture, such every bit the Farnese Hercules in gold terracotta.

Grotesques [edit]

In a completely different genre, at that place are the "grotesques", which dissimilarity violently with the canons of "Greek beauty": the koroplathos (figurine maker) fashions deformed bodies in tortuous poses – hunchbacks, epileptics, hydrocephalics, obese women, etc. Ane could therefore wonder whether these were medical models, the town of Smyrna existence reputed for its medical school. Or they could merely be caricatures, designed to provoke laughter. The "grotesques" are every bit common at Tarsus and besides at Alexandria.

Negro [edit]

One theme which emerged was the "negro", specially in Ptolemaic Egypt: these statuettes of Black adolescents were successful up to the Roman period.[77] Sometimes, they were reduced to echoing a form from the bang-up sculptures: thus one finds numerous copies in miniature of the Tyche (Fortune or Adventure) of Antioch, of which the original dates to the commencement of the 3rd century BC.

Hellenistic pottery designs can exist constitute in the city of Taxila in modern Pakistan, which was colonized with Greek artisans and potters later Alexander conquered it.

-

Female head partially imitating a vase (lekythos), 325-300 BC.

-

Ancient Greek terracotta head of a beau, found in Tarent, ca. 300 BC, Antikensammlung Berlin.

-

Tanagra figurine playing a pandura, 200 BC

Minor arts [edit]

Metallic art [edit]

Because of and so much bronze statue melting, only the smaller objects still exist. In Hellenistic Greece, the raw materials were plentiful following eastern conquests.

The work on metallic vases took on a new fullness: the artists competed amid themselves with nifty virtuosity. The Thracian Panagyurishte Treasure (from modernistic Bulgaria), includes Greek objects such as a gold amphora with two rearing centaurs forming the handles.

The Derveni Krater, from near Thessaloniki, is a big bronze volute krater from well-nigh 320 BC, weighing 40 kilograms, and finely decorated with a 32-centimetre-tall frieze of figures in relief representing Dionysus surrounded by Ariadne and her procession of satyrs and maenads.[78] The neck is decorated with ornamental motifs while four satyrs in loftier relief are casually seated on the shoulders of the vase.

The development is similar for the art of jewelry. The jewelers of the time excelled at treatment details and filigrees: thus, the funeral wreaths present very realistic leaves of trees or stalks of wheat. In this period the insetting of precious stones flourished.

Drinking glass and glyptic fine art [edit]

It was in the Hellenistic period that the Greeks, who until then only knew molded glass, discovered the technique of glass blowing, thus permitting new forms. Showtime in Syria,[79] the art of glass developed especially in Italia. Molded glass continued, notably in the cosmos of intaglio jewelry.

The art of engraving gems inappreciably advanced at all, limiting itself to mass-produced items that lacked originality. As compensation, the cameo made its appearance. Information technology concerns cut in relief on a rock equanimous of several colored layers, allowing the object to be presented in relief with more than one color. The Hellenistic period produced some masterpieces like the Gonzaga cameo, now in the Hermitage Museum, and spectacular hardstone carvings similar the Loving cup of the Ptolemies in Paris.[80]

Coinage [edit]

Coinage in the Hellenistic period increasingly used portraits.[81]

-

The aureate larnax of Philip Two of Macedon which contained his remains. It was synthetic in 336 BC. Information technology weighs eleven kilos and is made of 24 carat aureate. Vergina, Greece.

-

The golden wreath of Philip Ii found within the golden larnax. Information technology weighs 717 grams.

-

The Gonzaga Cameo tertiary century BC, in the Hermitage Museum, Saint petersburg

-

Apollonios of Athens, gold ring with portrait in garnet, c. 220 BC

Later Roman copies [edit]

Spurred by the Roman acquisition, elite consumption and demand for Greek art, both Greek and Roman artists, specially after the establishment of Roman Greece, sought to reproduce the marble and statuary artworks of the Classical and Hellenistic periods. They did then past creating molds of original sculptures, producing plaster casts that could be sent to whatsoever sculptor's workshop of the Mediterranean where these works of art could be duplicated. These were frequently faithful reproductions of originals, however other times they fused several elements of various artworks into i group, or simply added Roman portraiture heads to preexisting athletic Greek bodies.[82]

-

Drunken old woman clutching a lagynos. Marble, Roman copy after a Greek original of the second century BC, credited to Myron.

-

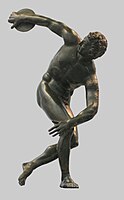

Roman statuary reduction of Myron'southward Discobolos, 2nd century Advert

-

-

Child playing with a goose. Roman copy (1st–2nd centuries AD) of a Greek original, in the Louvre.

-

The Tyche of Antioch. Roman copy subsequently a Greek bronze original by Eutychides of the 3rd century BC.

-

Old market woman, Roman artwork after a Hellenistic original of the second century BC.

-

Crouching Aphrodite, marble copy from the 1st century BC afterward a Hellenistic original of the third century BC.

-

Artemis of the Rospigliosi type. Marble, Roman artwork of the Imperial Era, 1st–2d centuries Ad. Copy of a Greek original, Louvre

-

The Farnese Hercules, probably an enlarged copy made in the early 3rd century AD and signed by a certain Glykon, from an original by Lysippos (or 1 of his circumvolve) that would have been made in the 4th century BC; the copy was fabricated for the Baths of Caracalla in Rome (dedicated in 216 Advertising), where it was recovered in 1546

See as well [edit]

- Alexander the Great

- Hellenistic civilisation

- Hellenistic Hellenic republic

- Hellenistic menses

- Art in aboriginal Greece

- Pottery of Ancient Greece

- Ancient Greek vase painting

- Greek sculpture

- Hellenistic influence on Indian art

- Parthian art

- Bacchic art

References and sources [edit]

- References

- ^ a b Pedley, p. 339 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPedley (help)

- ^ Burn, p. 16 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBurn (help)

- ^ Pollitt, p. 22 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPollitt (aid)

- ^ Bolman 2016, pp. 120–121

- ^ Winter, p. 42

- ^ Anderson, p. 161 harvnb fault: no target: CITEREFAnderson (aid)

- ^ Havelock, p. ? harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHavelock (aid)

- ^ Pedley, p. 348 harvnb fault: no target: CITEREFPedley (help)

- ^ Cahill, Nicholas (2002). Household and City Organization at Olynthus. Yale Academy Printing. pp. 74–78. ISBN9780300133004.

- ^ Burn, p. 92 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBurn (help)

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History (XXXIV, 52)

- ^ a b Richter, p. 233 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRichter (help)

- ^ Smith, 33–40, 136–140

- ^ Paul Lawrence. "The Classical Nude". p. 5.

- ^ Smith, 127–154

- ^ Green, pp. 39–forty harvnb mistake: no target: CITEREFGreen (help)

- ^ Boardman, p. 179 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBoardman (help)

- ^ Studies in the History of Fine art. National Gallery of Fine art. i January 1999. ISBN9780300077339 – via Google Books.

- ^ Winter, p. 235

- ^ Paul Lawrence. "The Classical Nude". p. 4.

- ^ Boardman, 199

- ^ Pollitt, p. 110 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPollitt (help)

- ^ Richter, p. 234 harvnb fault: no target: CITEREFRichter (help)

- ^ Singleton, p. 165 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSingleton (help)

- ^ "Scientific American". Munn & Company. 1 January 1905 – via Google Books.

- ^ Burn down, p. 160 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBurn (assistance)

- ^ a b c Pedley, p. 371 harvnb fault: no target: CITEREFPedley (help)

- ^ Lessing contra Winckelmann

- ^ Richter, p. 237 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRichter (help)

- ^ Klein, Wilhelm (1921). Vom antiken Rokoko (in German language). Hölzel: Österreichische Verlagsgesellschaft.

- ^ Klein, Wilhelm (1909). "Dice Aufforderung zum Tanz. Eine wiedergewonnene Gruppe des antiken Rokoko". Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst. 20: 101–108.

- ^ Habetzeder, Julia (1 November 2021). "The Invitation to the Dance. An intertextual reassessment". Opuscula. Almanac of the Swedish Institutes at Athens and Rome. xiv: 419–463. doi:10.30549/opathrom-14-19. ISSN 2000-0898. S2CID 239854909.

- ^ Junker, Klaus (2008). Original und Kopie. Formen und Konzepte der Nachahmung in der antiken Kunst (in German). Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag. pp. 77–108. ISBN978-iii-89500-629-6.

- ^ Smith, 240–241

- ^ Smith, 258–261

- ^ a b Pedley, p. 377 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPedley (aid)

- ^ "Emory Libraries Resources Terms of Use - Emory University Libraries". ebookcentral.proquest.com . Retrieved xvi November 2018.

- ^ Schefold, Karl (Summer 1960). "Origins of Roman Landscape Painting". The Art Bulletin. 42 (2): 87–96. doi:10.1080/00043079.1960.11409078. JSTOR 3047888.

- ^ Ling, Roger (1977). "Studius and the Ancestry of Roman Mural Painting". The Journal of Roman Studies. 67: ane–xvi. doi:10.2307/299914. JSTOR 299914.

- ^ "Wind Towers in Roman Wall Paintings" (PDF). metmuseum.org . Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ Rostovtzeff, Grand. (1919). "Aboriginal Decorative Wall-Painting". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 39: 144–163. doi:10.2307/624878. JSTOR 624878.

- ^ a b Rostovtzeff, M (1919). "Aboriginal Decorative Wall-Painting". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 39: 144–163. doi:10.2307/624878. JSTOR 624878.

- ^ a b Abbe, Mark B. "Painted Funerary Monuments from Hellenistic Alexandria". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pfmh/hd_pfmh.htm (April 2007)

- ^ http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hard disk drive/haht/hd_haht.htm

- ^ a b c d e f Kakoulli, Ioanna (2002). "Late Classical and Hellenistic painting techniques and materials: a review of the technical literature". Studies in Conservation. 47 (Supplement-1): 56–67. doi:x.1179/sic.2002.47.Supplement-i.56. ISSN 0039-3630. S2CID 191474484.

- ^ a b Palagia, Olga. ""THE Regal Court IN Aboriginal MACEDONIA: THE EVIDENCE FOR ROYAL TOMBS," in A. Erskine et al. (eds.), The Hellenistic Court (Bristol 2017)".

- ^ Pollitt, p. 40 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPollitt (assistance)

- ^ a b Alberge, Dalya (21 August 2010). "Discovery of ancient cavern paintings in Petra stuns art scholars". The Observer . Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ Fowler, Harold N; Wheeler, James Rignall; Stevens, Gorham Phillips (1909). A Handbook of Greek Archeology. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. ISBN9780819620095.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh (1913). The Britannica Year Volume. Encyclopœdia Britannica Company, Limited.

- ^ Bruno, p. one harvnb fault: no target: CITEREFBruno (help)

- ^ a b Bruno, Vincent J. (1985). Hellenistic Painting Techniques: The Prove of the Delos Fragments. BRILL. ISBN978-9004071599.

- ^ Harding, Catherine (2003). "Mosaic | Grove Fine art". one. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t059763. ISBN978-1-884446-05-4 . Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d due east Harding, Catherine (2003). "Mosaic | Grove Art". 1. doi:x.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t059763. ISBN978-1-884446-05-iv . Retrieved 28 Nov 2018.

- ^ Dunbabin, Katherine M. D. (1979). "Technique and Materials of Hellenistic Mosaics". American Periodical of Archaeology. 83 (three): 265–277. doi:10.2307/505057. JSTOR 505057. S2CID 193097937.

- ^ Wootton, Will (Leap 2012). "Making and Significant: The Hellenistic Mosaic from Tel Dor". American Periodical of Archæology. 116 (2): 209–234. doi:10.3764/aja.116.2.0209. JSTOR 10.3764/aja.116.ii.0209. S2CID 194498598.

- ^ a b c Wooton, Will (2012). "Making and Significant: The Hellenistic Mosaic from Tel Dor". American Journal of Archaeology. 116 (2): 209–234. doi:10.3764/aja.116.2.0209. JSTOR x.3764/aja.116.2.0209. S2CID 194498598.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History (XXXV, 110)

- ^ Kleiner, p. 142 harvnb fault: no target: CITEREFKleiner (aid)

- ^ Mosaics of the Greek and Roman earth By Katherine M. D. Dunbabin pg. 14

- ^ Chugg, Andrew (2006). Alexander's Lovers. Raleigh, Due north.C.: Lulu. ISBN 978-1-4116-9960-one, pp 78–79.

- ^ a b Kleiner and Gardner, pg. 135

- ^ "The history of mosaic art".

- ^ a b c Kleiner and Gardner, pg. 136

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History (XXXVI, 184)

- ^ "Asarotos oikos: The unswept room".

- ^ a b c "Art and sculptures from Hadrian'south Villa: Mosaic of the Doves". Following HADRIAN. thirteen June 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Havelock, p. ? harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHavelock (assist) [ verification needed ]

- ^ a b Chamoux 2002, p. 375

- ^ Christopoulos, Lucas (Baronial 2012). "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)", in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230. Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Academy of Pennsylvania Section of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. ISSN 2157-9687, pp. xv–16.

- ^ Fletcher, Joann (2008). Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend. New York: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-058558-7, image plates and captions between pp. 246-247.

- ^ Pedley, p. 382 harvnb fault: no target: CITEREFPedley (aid)

- ^ Burn, p. 117 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBurn (help)

- ^ Pedley, p. 385 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPedley (assistance)

- ^ Von Bothner, Dietrich, Greek vase painting, p. 67, 1987, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, Northward.Y.)

- ^ Masseglia, p. 140 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMasseglia (assistance)

- ^ Iii Centuries of Hellenistic Terracottas

- ^ Burn, p. 30 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBurn (assist)

- ^ Honour, p. 192 harvnb fault: no target: CITEREFHonour (help)

- ^ Pollitt, p. 24 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPollitt (help)

- ^ "Hellenistic Money Portraits".

- ^ Department of Greek and Roman Art (Oct 2002). "Roman Copies of Greek Statues." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ Capitoline Museums. "Colossal statue of Mars Ultor also known as Pyrrhus - Inv. Scu 58." Capitolini.info. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- Sources

- This article draws heavily on the fr:Art hellénistique article in the French-linguistic communication Wikipedia, which was accessed in the version of x November 2006.

- Anderson, William J. (ane June 1927). The Architecture of Ancient Greece. London: Harrison, Jehring, & Co. ISBN978-0404147259.

- Boardman, John (1989). Greek Art . London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN978-0-500-20292-0.

- Boardman, John (18 Nov 1993). The Oxford History of Classical Art. Oxford Academy Press. ISBN0-nineteen-814386-9.

- Bolman, Elizabeth S. (2016). "A Staggering Spectacle: Early Byzantine Aesthetics in the Triconch". In Bolman, Elizabeth Due south. (ed.). The Cherry-red Monastery Church: Beauty and Divineness in Upper Egypt. New Oasis & London: Yale University Printing; American Enquiry Center in Egypt, Inc. pp. 119–128. ISBN978-0-300-21230-3.

- Bruno, Vincent 50. (1985). Hellenistic Painting Techniques: The Evidence of the Delos Fragments. ISBN978-9004071599.

- Burn, Lucilla (2005). Hellenistic Fine art: From Alexander The Great To Augustus. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Trust Publications. ISBN978-0-89236-776-4.

- Chamoux, Françios (2002) [1981]. Hellenistic Culture. Translated by Michel Roussel. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN978-0631222422.

- Charbonneaux, Jean, Jean Martin and Roland Villard (1973). Hellenistic Greece. Peter Green (trans.). New York: Braziller. ISBN978-0-8076-0666-seven.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link) - Light-green, Peter (nineteen October 1993). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age . ISBN978-0520083493.

- Havelock, Christine Mitchell (1968). Hellenistic Art . Greenwich, Connecticut: New York Graphic Lodge Ltd. ISBN978-0-393-95133-2.

- Holtzmann, Bernard and Alain Pasquier (2002). Histoire de 50'art antiquarian: fifty'fine art grec. Réunion des musées nationaux. ISBN978-two-7118-3782-3.

- Laurels, Hugh (2005). A World History of Art. ISBN978-1856694513.

- Kleiner, Fred S. (2008). Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Global History. Cengage Learning. ISBN978-0-495-11549-6.

- Masseglia, Jane (2015). Body Language in Hellenistic Art and Society. ISBN978-0198723592.

- Pedley, John Griffiths (2012). Greek Art and Archaeology. ISBN978-0-205-00133-0.

- Pollitt, Jerome J. (1986). Fine art in the Hellenistic Age. Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN978-0-521-27672-6.

- Richter, Gisela Chiliad. A. (1970). The Sculpture and Sculptors of the Greeks .

- Singleton, Esther (1910). Famous sculpture as seen and described by groovy writers. Dodd, Mead & Company.

- Stewart, Andrew (2014). Art in the Hellenistic Earth: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-1-107-62592-1.

- Wintertime, Frederick. Studies in Hellenistic Compages. ISBN978-0802039149.

- Zanker, Graham (2004). Modes of Viewing in Hellenistic Poesy and Art. University of Wisconsin Printing. ISBN978-0299194505.

Farther reading [edit]

- Anderson, Jane E. A. Torso Language in Hellenistic Fine art and Guild. Start edition. Oxford: Oxford University Printing, 2015.

- Stewart, Andrew F. Art in the Hellenistic World: An Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Trofimova, Anna A. Imitatio Alexandri in Hellenistic Art: Portraits of Alexander the Cracking and Mythological Images. Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider, 2012.

- Zanker, G. Modes of Viewing in Hellenistic Poetry and Art. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004.

External links [edit]

- Selection of Hellenistic works at the British Museum

- Pick of Hellenistic works at the Louvre

- Hellenistic Fine art, Ancient-Hellenic republic.org

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hellenistic_art

0 Response to "What Are the Major Ways in Which Hellenistic Art Differs From Classical Art?ã¢â‹"

Enviar um comentário